Part A Protecting Project Margins: Loss-Making Contracts And The Reasons They Happen

Every contractor would probably turn around and say that if they could get rid of the one or two really bad loss-making contracts, generally speaking, everything would be alright.

As an industry, we're talking about legacy. But what do we mean when we talk about legacy? A ‘legacy contract' has become a term to bundle up contracts that have lost lots of money and say, “that will never happen again, that was just a point in time, and going forward, we will obviously do things better, we won't make the same mistakes again!”

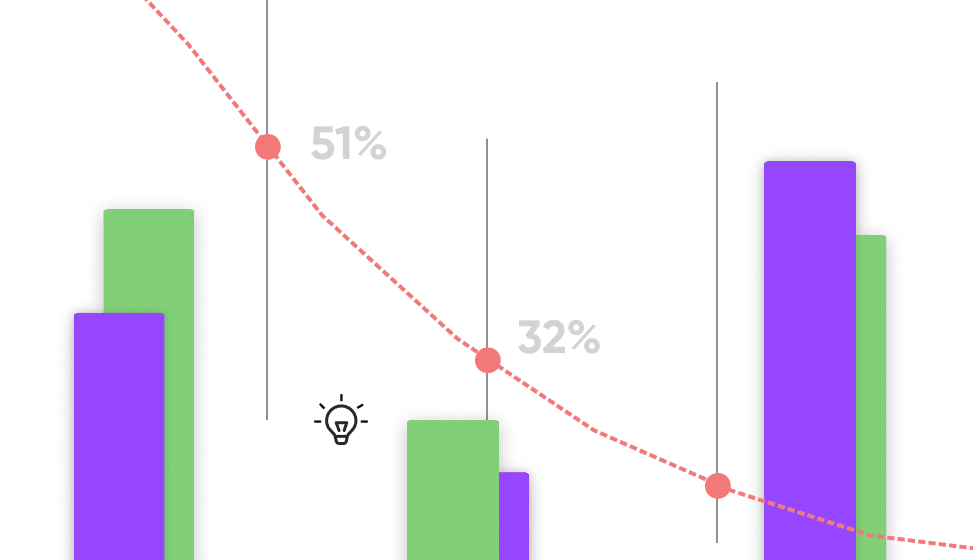

In general, construction companies have one or two jobs that are performing badly, but the rest are ok. If you get that right, your net margin sits somewhere between 0 and 3%. The balance tips, when those jobs become a higher percentage of your sales, or your sales projection starts to drop, volume is reduced, and they become a more significant part of the portfolio. That's why balancing your portfolio can't just depend on avoiding the bad projects but taking a look at the good ones and saying, “what can we do better?”

As an industry, we still tend to get more right than wrong. But when we get things wrong, we get things really wrong. Errors continue to compound themselves, and bad contracts turn ugly.

Setting Margins – Why So Low?

There's a science to pricing a construction project; you look in great detail at the schedule, your supply chain pricing, and the design development. You base the price on cost and add the margin you think you can win the job on. Once you secure the project, any improvement in margin is limited, and everything that happens tends to take the profit down; the design wasn't developed enough, you end up paying more for your supply chain, and so on and so forth. There's a whole series of things that knock the margin, and when a project goes badly, all the bad things happen.

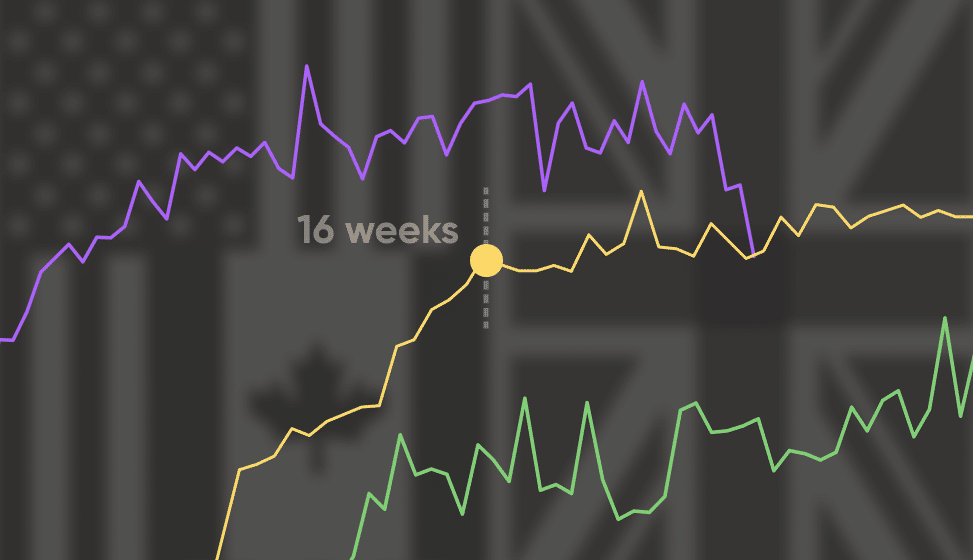

The margins you set depend on the economy and who you're competing against; it's straight supply and demand. If people are busy, you increase your margins, if the economy is in a downturn, you lower them – because the construction model needs sales. The whole model rotates around cash flow, and cash is the hardest thing to predict for a construction project. If you don't get the turnover, you don't generate the cash, and you find yourself in a difficult position because of your overhead costs.

The high competition stems from the construction industry's low barrier to entry. If you remove the more sophisticated designs that require specialist contractors, there's a very low capital requirement. It's only the first few weeks of a construction project that you need to be able to generate cash. So if you can organize cash flow to cover the first one or two projects, you can get up and running as a construction company. It's why companies can be created so quickly.

This results in the industry's low margins, there is always somebody else who would simply come in and take the work from you. And the thing that kills a construction company, that kills any company, is running out of cash. But in construction, once you're on the treadmill, it's very hard to get off. You can't just stop because you have commitments to complete projects, and you end up eating even further into your cash. As you're completing a project, unless you've got the next one coming up, it's really difficult to manage your cash flow forecast. So, staying on track of project progress can really break or make a company.

Key Takeaways:

- The Industry needs to manage cash flow to deal with the impact of peaks and troughs of workload

- Staying on top of project progress is key to managing your cash flow

Becoming A Margin Killer Project?

It's relatively straightforward what kills projects. One of the main reasons happens before the work even begins… underestimating the design complexity means you underestimate the resources required to manage the project, which means you've underestimated the time needed to build the project. It's why procurement moved from single-stage to two-stage, to give contractors more time to understand the complexity of the design. Nevertheless, we still build projects with incomplete designs.

A lot of the industry's issues stem from incomplete design. One of the big advantages of Buildots is it drives the need for more detailed design earlier.

Once you have an incomplete design, you're always going to be late in procuring the supply chain because you don't know exactly what you're placing the order for. We have a very fragmented supply chain, and it's very volatile in terms of its financial security – if you have a major failure of a supply chain partner, that really impacts the project. And the processes slowly start to unravel.

Key Takeaways:

- Having an incomplete design when starting construction increases risk during the project

- Deploying Buildots focuses teams to get the design completed earlier; thereby reducing risk.

Acting In The Grey

Your plasterer is being held up by the electrician. The electrician should have started two months earlier but couldn't because the work wasn't ready, but you expect him to catch up the time. He's holding up the plasterer, but the plasterer isn't actually held up. He's not got the resources because he is too stretched working on other jobs but is using the excuse that the electrician is holding him up. It's this whole massively grey world that we live in, where you're trying to understand what is actually happening.

During construction, there are many things that can go wrong. You don't get the resource level from your supply chain; they say it's because the project is not sufficiently developed, so they can't put the resources on it that they were planning to. It's always somebody else's fault, and we spend a lot of time arguing over whose fault it is. We then spend a lot of time trying to justify how the delay is due to a change made by the customer; therefore, they should pay the extra cost. In reality, some of the cost should go to the subcontractor and some to you because you didn't place the order early enough. As we can't prove whose fault it is, we spend time and money employing resources to get the answers, but they increase overhead costs and don't fix the problem.

Some companies stop taking on certain types of work because they've had bad experiences. For example, residential projects tend to be smaller units, and there's only a certain number of resources you can put into a physical space. This means you can only do X number of bathrooms at X speed. If you start to get the sequencing wrong, then you don't move through the building in a natural way. Quite often, once you start having problems, you end up working on all floors, all over the place; this leads to inefficient use of resources and materials, and the inefficiency costs money.

During the postmortem, we say, “We won't make the same mistake again because we've got rid of the project manager, and it was all his fault because he let the project run out of control.” There'll be a degree of that, a degree of pricing errors, and a degree of taking on bad contracts because the company was desperate for work. But a lot of it comes down to blaming the site team. There is a high blame culture, and it's based on the fact that what is being reported is subjective, and the situation on-site is grey.

Key Takeaways:

- We spend a lot of time and resources looking back on contracts to try and understand what went wrong and whose fault it was.

- Life would be a lot easier if we had the data available throughout the project

“Scheduled False Hope”

You're working on a residential contract. Preparations for the project were a long time in the making; you've scheduled it, you've planned it, you've looked at the design, you've done everything, and then halfway through, you're running behind. How did this happen? Because until then, “false hope” set in, but at some point, the problems became too big to hide. Two years of hard work get thrown out the window, and suddenly… “we can do the plastering in five weeks, not ten!” But if we could have done it in five weeks, then when we had all that time in the world to look and analyze it, we'd have scheduled five weeks?! But no, we accelerate it, bring in another subcontractor and change the critical path on the project so we can still hit the original dates.

It's a very human thing. You look at something that's delayed and give yourself all sorts of explanations as to why it happened. You convince yourself that everything is going to be fine if you just do more here and work better there. There's always an explanation as to why the project is not in such a bad situation. Yes, there are things we can change, we are solution finders, but more often than not, it doesn't happen. And we upset customers all the time because we're not telling them the truth, and they can't plan. At the end of the project, you sit with the customer and hear, “If only you would have told me you were going to be another four weeks, we could have done x, y and z. You cost us money, we lost tenants, we lost sales.”

But what tends to happen is we look at a project and immediately say we need to double the resources on it. So we go to the subcontractor, and they provide the additional labour and resources, and at the end of it, we receive a whopping big bill that's vastly more than you thought. But you asked them to accelerate work, and whereas you were expecting ten men on it, they've ended up with twenty men on it, and there's a cost to that. So, you end up with claims, and it's another one of the big killers on construction margins. The bills keep coming in, you try to push the extra costs onto another party but get left holding the baby. Ultimately, the main contractor has to pick up the bill.

Key Takeaways:

- Don't get lulled into a false sense of security

- Today there are ways to capture accurate data, so why aren't you using them?

Enjoyed reading Part A of our Protecting Project Margin series, but wondering what now? Check out Part B.